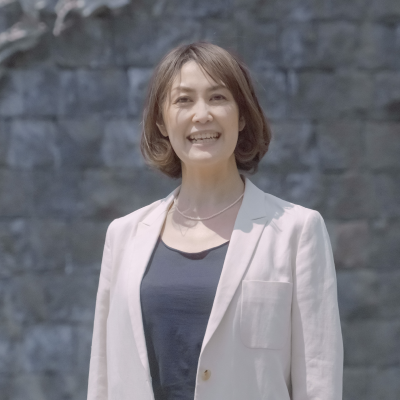

垣内 陽子さん

昨年度まで5年間、札幌芸術の森の魅力の発信、施設の新たな利用の検討、実施に取り組んできた。4月より市内中心部にある札幌市民交流プラザに勤務。

公益財団法人札幌市芸術文化財団

市民交流プラザ事業部 管理課 業務係長

垣内 陽子さん

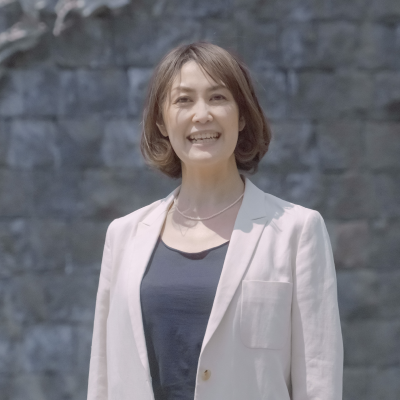

公益財団法人札幌市芸術文化財団

芸術の森事業部 管理課 業務係

山口 万柚子さん

ヘラルボニー

アカウント事業部 プランナー

阿部 麗実

ヘラルボニー

ウェルフェア事業部 コンテンツクリエイター

菊永 ふみ

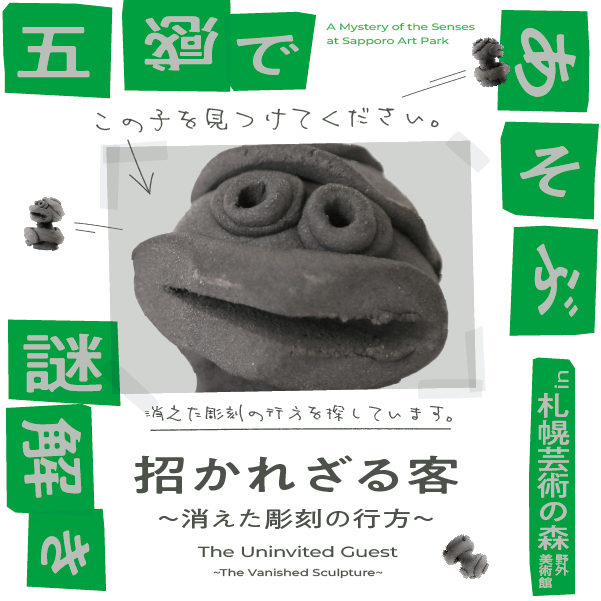

北海道札幌市の札幌芸術の森野外美術館で、

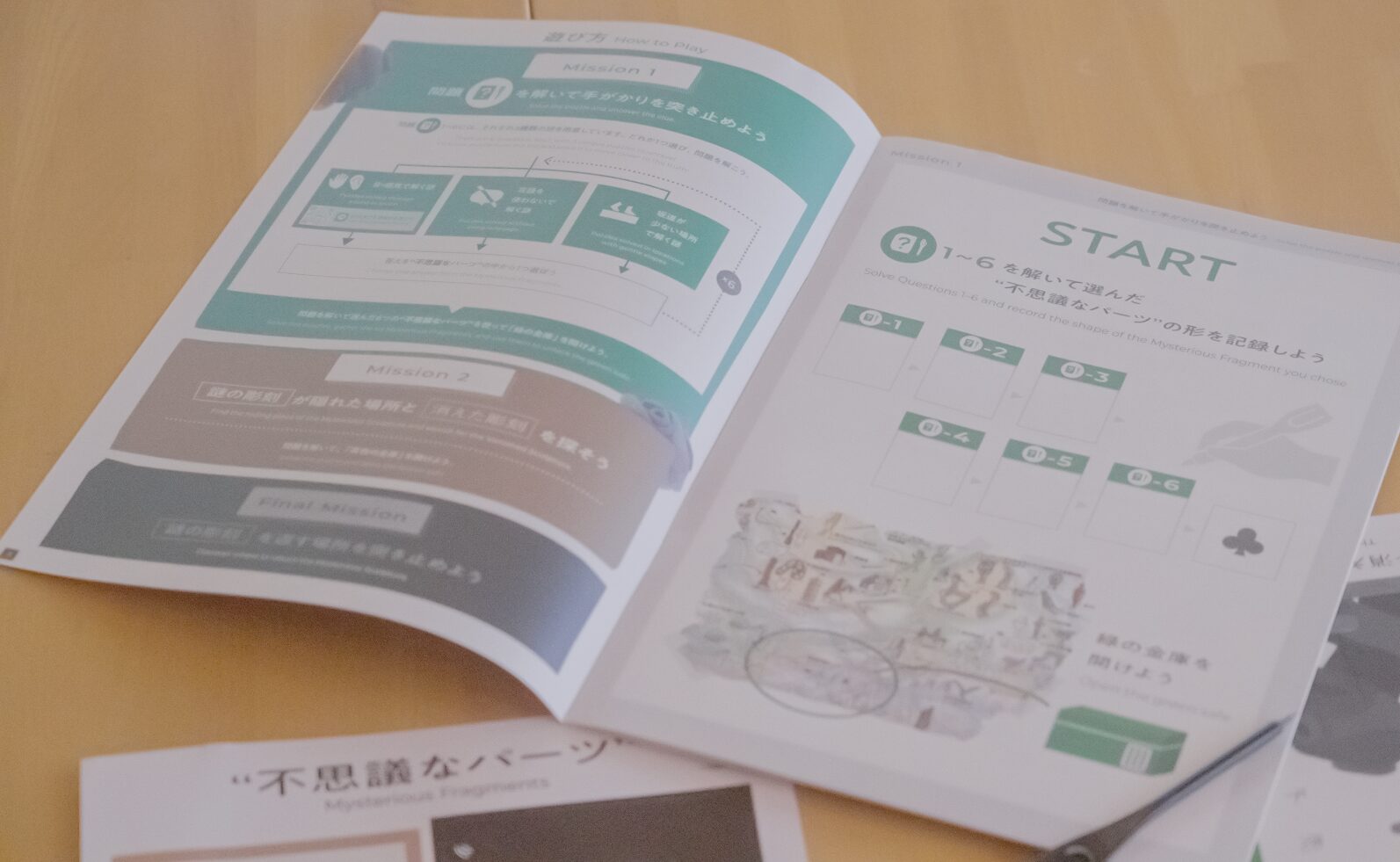

ヘラルボニーが制作した新しい体験コンテンツ「五感であそぶ謎解き」が公開されました。

彫刻や自然に囲まれた空間の中で、外国の方も、障害のある方も、長距離の移動が難しい方も、それぞれのやり方で、同じゴールを目指すことができます。

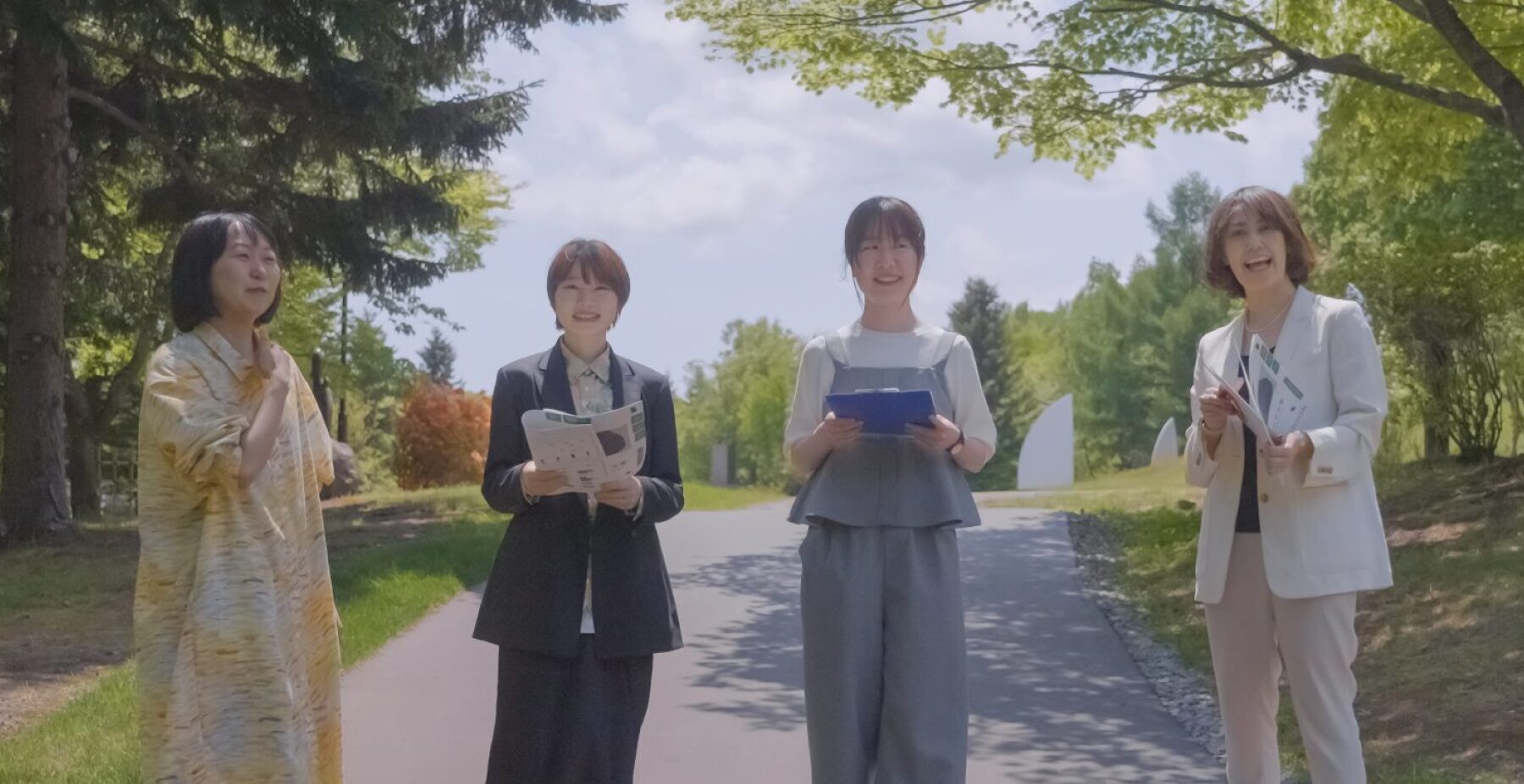

このプロジェクトについて、公益財団法人札幌市芸術文化財団の垣内陽子さん・山口万柚子さんと、ヘラルボニーの阿部麗実・菊永ふみの4名が振り返ります。

制作過程で交わされた議論や、テストプレイで生まれた気づきの数々は、

アクセシビリティの枠を超え、「誰もが楽しめる」とは何か?をあらためて考える時間になりました──。

まず、今回の「五感であそぶ謎解き」の企画に至った経緯をあらためてお聞かせください。

垣内さん

昨今海外からのインバウンド需要も戻ってきたということで、海外からの観光旅行者を取り込めないかというのが最初の課題でした。でもヘラルボニーの皆さんと議論をしているうちに、今までの謎解きの中で「これまで届かなかった人」がいるということに気づいたんです。それは外国の人だけじゃない。もっと可能性を広げていったらどうなのか、という話になりました。

阿部

ヘラルボニーのメンバーで初めて芸術の森に行った際、彫刻の作品名を想像して当てるゲームをしながら歩いたのですが、私が感じる彫刻のイメージと他のメンバーが感じるイメージが全然違う。それってすごく面白いことだよね、と会話していました。

例えば、子どもの視点で見たらもっと違う楽しみ方があるのではないか。さまざまな方が楽しめる謎解きになれば、もっと面白くなると思いました。

菊永

普通の美術館だと「作品に触ったらダメ」というルールがありますが、芸術の森野外美術館の彫刻の場合は、実際に見て触ることができます。作品だけではなく、敷地内にある川や木などの自然が一緒になって一体感を感じられるのが、この美術館の魅力だと思うんです。

音だったり、見た目だったり、触覚だったり…五感を使えるので、さまざまな方々を受け入れることができる空間になるのではないかと感じました。

垣内さん

自分たちが毎日見ていると気づかなくなってしまうような施設の魅力を提案いただきました。ヘラルボニーだからこその見方で、海外の観光客向けというところからより広がっていったアイディアをいただけたのは大変ありがたかったです。

さまざまな方に届けるために、どのような工夫を考えたのでしょうか?

阿部

野外美術館は(自然の中に彫刻作品があり、)山道など足元が不安定な場所が多いため、例えばベビーカーでいらっしゃる方や、足腰の弱い方、お子様連れの方が「上に登れなかった」という課題もありました。こうした課題に加え、視覚に障害があったり、聴覚に障害があったりする方々も一緒に楽しくあそぶことができる謎解きを作るために、複数の体験導線を用意し、解く人自身の状況や好みに合わせて選択できる仕組みを開発しました。

従来の謎解きイベントは、与えられる問題は一つであり、これに対して障害があるとそもそも問題自体にアクセスできない人がいました。今回、「音・触覚で解く謎」「言語を使わないで解く謎」「坂道が少ない場所で解く謎」の3つの問題(どれを解いても答えは同じになる)を用意しています。

菊永

私はろう者なので、当然音のない世界にいます。視覚障害のある方は音を聞きながら謎解きを進めることができますが、ろう者は音を使う謎の回答には絶対にたどり着けません。

それぞれの世界の見方、考え方、捉え方は違います。そのありのままの人たち同士で、どうやって受け入れられる・認められる方法を作るかを考えたときに、複数のアプローチが良いのではないかという結論に至りました。

制作過程で最も苦労されたのはどのような点でしょうか?

垣内さん

私たちは現場でお客様に接する立場なので、最初の段階では「本当に目の見えない方が解けるのか」という不安がありました。当事者の方にお見せした時に受け入れてもらえるのか。どこまでいっても想像するしかない部分があって、そこに自信がもてなかったのです。

阿部

私と菊永さんで謎を作っていても、例えば視覚に障害のある方がどんな課題を感じているかは、やっぱり想像でしかありません。なので、リアルな声を聞きながら作っていくことがすごく大事だと思いました。

例えば、石井健介さんというブラインドコミュニケーターの方に監修をお願いしました。また、ある程度謎ができた段階で、実際にさまざまな方を呼んでテストプレイをしていただきました。その結果、車椅子を利用する方、ろう者の方、外国籍の方などにご意見をいただきながらアップデートしていく形になりました。

垣内さん

でも石井さんが「わからなかったり、必要か必要じゃないか悩んだりしたら、聞いてくれたらいい」とおっしゃってくださったので、そこからは2日間、「ここに行けますか」「何が必要ですか」などたくさん質問しました。

例えば、付き添いスタッフを用意した方が良いのかという検討もあったのですが、「知らない人といきなり2人きりにされる方が困る」という話もあり、それはそうだよなと。私たちが良かれと思っていたことが、意外に独りよがりだったり…ということもありました。

障害のある方に参加いただくにあたって、最初は「音声案内を用意しなければいけない」とか「ガタガタな園路を整備したり、ハード面を整理しなければいけない」と考えていました。

でも、私たち職員として障害の垣根を飛び越えて、いろいろな方たちを受け入れる心の準備、さまざまな方を受け入れる意識を持つことが、ハード面以上に大切なんじゃないかということをテストプレイの時に感じました。

障害のある方を迎え入れようとしているにも関わらず、「気を悪くされるかもしれない」「傷つけてしまうのではないか」「失礼に当たってしまうのでは」と、コミュニケーションを取ることに消極的になっていました。

テストプレイの後、それまでのルールや環境についても見直しがあったと伺いました。

垣内さん

彫刻作品の特徴として、目で見るだけじゃなくて触覚で味わうということができるのが魅力なのですが、彫刻を触っていいかどうかは、美術館や施設によって考え方が異なります。

芸術の森野外美術館では、一部、触らないようにお願いしている彫刻作品がありました。今回、「五感であそぶ謎解き」の制作をきっかけに、企画意図を鑑み、禁止にはしない選択をすることにしました。

山口さん

道がガタガタになっている坂道も多くありました。元々は整った道でしたが、だんだん荒れて車椅子を利用する方は通れない場所になり、それが普通になってしまっていました。多くの方は問題なく通れたので、補修する優先順位がやっぱり下がってきてしまう。

今回の企画を進めるにあたってその意識の低さを変えることになり、通行しづらいという理由だけで、車椅子を利用する方たちがそこにある彫刻作品を見る機会を限定してしまっている状況を改善すべく、道路の整備も進めました。

また、ホームページの記載内容についても、ヘラルボニーにアクセシビリティチェックをしていただき、実は決まっていなかった対応方針が明確になりました。

また、お問い合わせが来た時に、運営に関わる全てのスタッフがさまざまな方をウェルカムする気持ちをきちんと持って接していく、できないことがあっても説明するという、気持ちの共有が大事だとわかりました。

実際にお客様からはどのような反応がありますか?

山口さん

ホームページを見て「車椅子でも参加できるイベントがある」と来ていただいた方も数名いますが、これからより発信を強めたいと思っています。

謎解きマニアの人が3種類全部、2時間で解いたというお客様もいて、「それぞれ感覚が違って楽しめた」という声もありました。

阿部

最初は車椅子の方を想定して企画をしていたところで、結果的に、ベビーカーでいらっしゃる方、小さいお子さま連れの方やご高齢の方にも対応できるようになりました。

「もっと小さな子どもにも体験させてあげたい」という声もいただいていて、言葉を使わない感覚的なものだと、全て解けなくてもチャレンジはできる。そういう良いところも副産物的に生まれました。

ちょっとした困りごとや、何かをやりたくてもできない状況は、「障害」だけが理由ではないはずです。今回は、ここにもアプローチできたのではないかと思います。

最後に、皆様が”アクセシビリティ”や”インクルーシブネス”というテーマについて、社会に伝えたいメッセージをお聞かせください。

山口さん

最初は芸術の森のことを皆さんに知ってもらいたいという思いで、多くの方に参加していただくためにイベントを始めました。でも実は、興味を持っても参加できていない人がいるということに改めて気付きました。

3種類のパターンを用意するとなった時も、最初は障害のある方向けの特別なコースを作るという考えしかありませんでした。そうではなく、その人の特性を生かしていろいろな解き方ができる場所になったのは、皆さんのおかげです。やっぱり障害の有無に関係なく一緒に楽しめるように、これからより一層ブラッシュアップしていければ良いなという思いでいます。

垣内さん

大事に思っているのは、本当は「同じ」ということに気付いた感覚です。私はろう者の菊永さんとの間にラインがある。でもそれは私と同じ聴者の阿部さんとの間にもあって、みんなの間にもあって、そのラインが消えはしないのだけど、短くなって通り抜けられるところがすごく増えていったような感覚があります。

石井さんの空間認知能力の高さのように、得意不得意みたいなことに似ているなと。あとは、相手とコミュニケーションを取っていく、その一歩踏み出すことが大切だと感じています。

菊永

当初、2024年のスタートを目指して進めていましたが、職員の皆様の心の面や設備のハード面も変えていこうと議論をして延期をしました。一つ一つ話し合い、検証をしていく作業は、普通の謎解きに比べたらかなり時間を要しました。でも、一人ひとりのちがいに向き合う感覚を受け止めながら作ることは、とにかく楽しかったです。

私はろう者なので、何かイベントがある時に「自分は参加していいのかな」ってやっぱり戸惑うんですよね。問い合わせをしないといけないのか、交渉しなきゃいけないのか、通訳は自分で用意しなきゃいけないのか、費用は私が払うのか、字幕はあるのかどうか…

今回のように「いいんですよ、私もあなたも誰でも来ていいんですよ」という肯定できる状況があるというのは、本当に一人ひとりの存在意義を肯定していることであり、大きな価値があると思います。

阿部

ヘラルボニーは、「障害」というものは社会側にあるという考え方をとっています。今決められたルールの中で、たまたまそれがその人にとって障害になっていくような状態だと考えると、見えてなかったいろんなものが見えてくると思います。

アクセシビリティのある、またインクルーシブな企画に取り組むことが、もっとフラットに物事を考えるきっかけにもなると思うので、そこで得られる視野の広がりや面白さを世の中に届けていくことによって、さまざまな方たちの視点も変わっていくことを目指していきたいです。

–

| 手話通訳: | 小松智美 |

|---|

イベントページはこちら(アクセシビリティ情報含む)

休憩スペースや多目的トイレなどのアクセシビリティ情報は公式ホームページにてご案内しています。

開催中:野外美術館 五感であそぶ謎解き【招かれざる客 ~消えた彫刻の行方~】 | 札幌芸術の森

昨年度まで5年間、札幌芸術の森の魅力の発信、施設の新たな利用の検討、実施に取り組んできた。4月より市内中心部にある札幌市民交流プラザに勤務。

芸術の森勤務3年目。昨年より、今回の謎解きイベント他、芸術の森園内の利用促進にかかる業務を担当。

脳神経科学を研究し博士号取得。乃村工藝社でミュージアムやヘルスケア空間等の企画・制作に従事。2023年よりHERALBONYへ。DE&Iを軸にしたコミュニケーションデザインや、空間・体験設計に取り組む。

異言語脱出ゲーム開発者。2018年に異言語Lab.設立。NHKなど多数とコラボし、体験型エンターテイメントを制作。ヘラルボニーではコンテンツ開発や障害者雇用推進を担当。

Google

プロダクト マーケティングマネージャー

松下実希さん

へラルボニー

アカウント事業部シニアマネージャー

國分さとみ